What can we do with the data collected?

The Kona Manta population provides a truly unique and exciting research opportunity found no where else in the world.

How so? Glad you asked. You may have heard the Kona manta dive origin story before. Lights from the Kona Surf Hotel shone into the shallow shore water near Keauhou Bay. This light attracted the plankton, and the plankton attracted the mantas - which could have been there all along anyway. Or not. Local dive shops started doing night dives at that location, and then eventually started offering them on a regular basis to diving tourists.

From there, everything grew and grew - the number of dive shops, the number of dives done, the number of boats, the number of tourists, and the number of sites to view mantas at. Due to the work of Manta Pacific Research Foundation (MPRF), the manta individuals were catalogued and made publicly available for review. First by a printed booklet, and then via a website. This allowed all of the operators to be able to help identify each of the unique individuals that showed up to each of the sites, and also allowed members of the public to identify them as well. Those reports of which mantas showed up where have been collected the whole time - this was one of the first "citizen science" projects around, before it was even a "thing"!

With the growth in popularity of this experience, it meant that someone was in the water each evening, almost 365 days a year. Kona's generally year round settled weather meant that operators could offer the experience year round as well. Which meant that reports could be gathered pretty much year round too. Reports consist of both the total number of mantas that show up at the site, and may or may not also include individual manta identifications as well.

And every now and again, no mantas will show up. One of the long running questions has been, why are there no mantas sometimes? To answer that question, you need to collect that data as well. Which we do! Nowhere else in the world would it make sense to have data collected where you had someone go in the water and say "Hey, note that I didn't see a manta". But the absence of mantas for us is a very interesting data point.

Originally, there was a theory that it was related to the moon phase. After reviewing the data though, this was discarded. Anecdotally, it seems to be related to the amount of plankton found in the water on a given night. But this could use more investigation.

We can do one pretty simple analysis though with our data. We can look at each month over the years and see if certain months are more popular than other months. Or really, if some months are more *un*popular with mantas than others. So we did that!

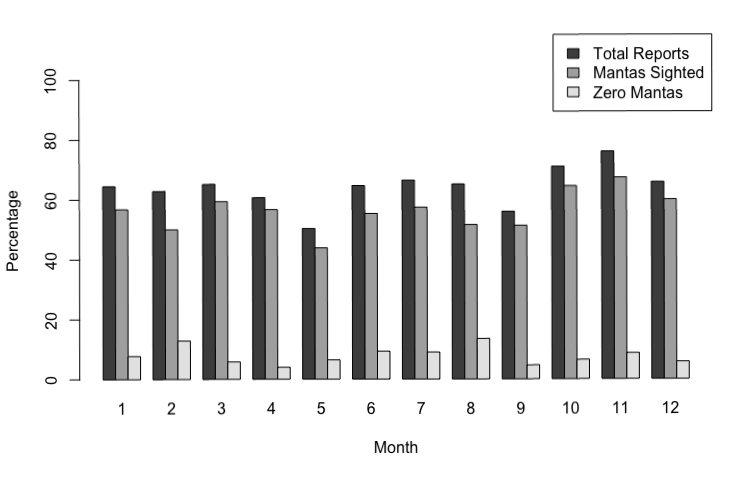

We looked at only 5 years worth of reports for one particular site - Makako Bay. For each month over those 5 years, we looked at what the total number of possible reports could be, the total number of reports submitted, the total number of reports that had any mantas sighted, and the total number of reports with zero mantas sighted.

Here it is:

The Kona Manta population provides a truly unique and exciting research opportunity found no where else in the world.

How so? Glad you asked. You may have heard the Kona manta dive origin story before. Lights from the Kona Surf Hotel shone into the shallow shore water near Keauhou Bay. This light attracted the plankton, and the plankton attracted the mantas - which could have been there all along anyway. Or not. Local dive shops started doing night dives at that location, and then eventually started offering them on a regular basis to diving tourists.

From there, everything grew and grew - the number of dive shops, the number of dives done, the number of boats, the number of tourists, and the number of sites to view mantas at. Due to the work of Manta Pacific Research Foundation (MPRF), the manta individuals were catalogued and made publicly available for review. First by a printed booklet, and then via a website. This allowed all of the operators to be able to help identify each of the unique individuals that showed up to each of the sites, and also allowed members of the public to identify them as well. Those reports of which mantas showed up where have been collected the whole time - this was one of the first "citizen science" projects around, before it was even a "thing"!

With the growth in popularity of this experience, it meant that someone was in the water each evening, almost 365 days a year. Kona's generally year round settled weather meant that operators could offer the experience year round as well. Which meant that reports could be gathered pretty much year round too. Reports consist of both the total number of mantas that show up at the site, and may or may not also include individual manta identifications as well.

And every now and again, no mantas will show up. One of the long running questions has been, why are there no mantas sometimes? To answer that question, you need to collect that data as well. Which we do! Nowhere else in the world would it make sense to have data collected where you had someone go in the water and say "Hey, note that I didn't see a manta". But the absence of mantas for us is a very interesting data point.

Originally, there was a theory that it was related to the moon phase. After reviewing the data though, this was discarded. Anecdotally, it seems to be related to the amount of plankton found in the water on a given night. But this could use more investigation.

We can do one pretty simple analysis though with our data. We can look at each month over the years and see if certain months are more popular than other months. Or really, if some months are more *un*popular with mantas than others. So we did that!

We looked at only 5 years worth of reports for one particular site - Makako Bay. For each month over those 5 years, we looked at what the total number of possible reports could be, the total number of reports submitted, the total number of reports that had any mantas sighted, and the total number of reports with zero mantas sighted.

Here it is:

5 years of night dive sightings at Makako Bay - 2019 thru 2023 inclusive

Let's look at couple of the numbers to help understand the chart.

At Makako Bay, we get reports for between 50% (#5 May) and 76% (#11 November) of the total possible number of nights for that month. Based on the total possible, the percentage of nights that mantas were sighted varies between 43% and 67%, but this will be weighted against those nights for which we have no data.

Month #2 and #8, February and August, have the highest percentage of seeing zero mantas at about 13% and 13.5% respectively.

At Makako Bay, we get reports for between 50% (#5 May) and 76% (#11 November) of the total possible number of nights for that month. Based on the total possible, the percentage of nights that mantas were sighted varies between 43% and 67%, but this will be weighted against those nights for which we have no data.

Month #2 and #8, February and August, have the highest percentage of seeing zero mantas at about 13% and 13.5% respectively.

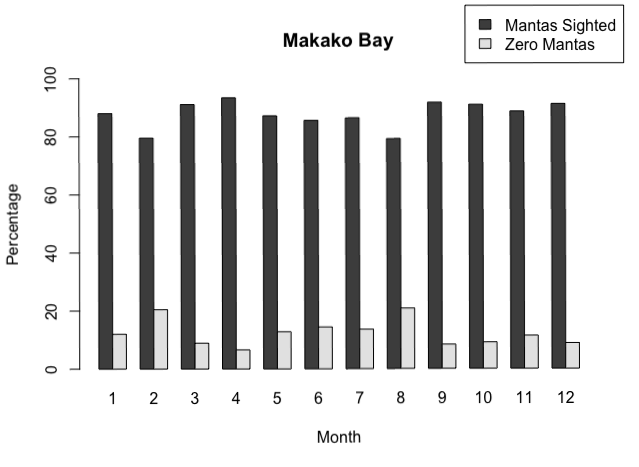

And February and August are the low months where again, you have an about 20% chance of NOT seeing a manta. This correlates with the chart above, just the numbers are scaled differently.

Next up? Well we really should look at more than 5 years of data. I wonder what 20 years worth of data would show ….